Prensa15.04.15

ACIJ / PrensaThe Other Buenos Aires: Villas and the Struggle for Urbanisation

15/04/15

By Kate Rooney

Gastón walked home from his first day of secondary school on a Monday afternoon, mid-March. The 13-year-old arrived, after playing “popcorn” with friends, to discover his cat trapped in a cesspit. In an effort to save the animal, he fell in too. Neighbours tried to pull the boy out and waited more than 40 minutes for an ambulance to arrive. By the time it did, Gastón had died.

Residents from his Rodrigo Bueno neighbourhood, nestled in the shadow of Puerto Madero’s shiny towers, blame a lack of urbanisation for Gastón’s death. Without proper infrastructure, preventable deaths are common in the villas miserias, or shantytowns, of Buenos Aires. These neighbourhoods are home to 163,587 people, according to the 2010 census, with today’s figure estimated to be much higher. With few exceptions, they lack sewer systems, roads, reliable electricity, and hospitals.

This absence of infrastructure is more than controversial. In Buenos Aires at least, it’s technically illegal.

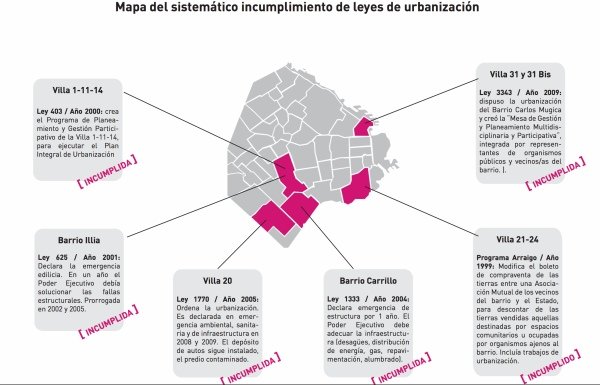

There are six laws that call on the city government to “urbanise” these neighbourhoods. As of 2015, none of them have been properly implemented. The most recent bill in 2009 was set to improve Villa 31, also minutes from Puerto Madero, bordering the famous Retiro train station.

That law gave the city government 180 days to start implementing urbanisation policies in Villa 31. But six years later, according to newly-elected delegate, Dora Mackoviak, little has changed.

She reclined on a blue lawn chair outside of her house, enjoying a cigarette after a long week of campaigning. Mackoviak, mother of ten, has been at the forefront of the urbanisation fight in her neighbourhood. Over the years she and her neighbours have earned the “fear and respect” of the city government.

“We have been fighting in this neighbourhood for a long time,” Mackoviak said. “We go out, we demand, we make noise.” She’s seen countless preventable accidents like Gastón’s in her own villa. Fires, electrical accidents, open cesspits, all hazards triggered by shoddy construction. The streets in most villas are too narrow and unfit for an ambulance or car. Even if paramedics can enter, they often won’t. Instead, they wait for a police escort and add significantly to response time. Mackoviak says neighbours sometimes volunteer their own cars instead of waiting for an ambulance.

Aside from preventable accidents, villa residents are also more likely to suffer from slower, less conspicuous health issues linked to a lack of urbanisation.

Joaquín Benítez, of non-partisan government oversight group ACIJ, explained the domino effect of human rights in the villas. Lead contamination, for example, is exacerbated by flooding, and is especially dangerous for children. These healthcare problems, he said, can’t be improved without urbanisation.

“They could have access to way more rights. They’d have proper water and sanitation infrastructure.” Deaths from preventable fires, caused by unsafe electric grids, he said, wouldn’t be an issue if urbanisation laws were implemented.

Mackoviak has been waiting years for these laws to bear fruit. Meanwhile, the city positions her and her neighbours as “the bogeyman”, she said. And while stigmas and fear of the villas continue to grow, the funds for resolving underlying problems continues to shrink.

Budgetary Nosedive

This year, the amount of money allocated from the city budget for urbanisation is the lowest in recent history.

Money for “vivienda”, or housing, has steadily declined over the past ten years, with only a slight uptick in 2010. In 2015, housing will receive 2.4% of public funds, making it the lowest amount in a decade. This money is reserved for anything from urbanising villas to helping the estimated 600,000 Buenos Aires residents living in emergency housing situations. One in six people in the capital, according to ACIJ, lives in an emergency situation and would theoretically receive that aid. ACIJ projects that only 0.6% of the city 2015 budget will be allocated to villas.

If past is prologue, most of these dwindling funds won’t be used. The city has a deep history of under-executing on social housing spending, and over-executing on works in tourist-dwelling areas like Palermo and Puerto Madero. In 2013, only 31% of allocated housing funds were actually spent. In 2014, only 28%. Meanwhile, last year, the city government was 78% over budget for government advertising, according to the 2015 ACIJ housing report.

Julian Bokser, psychology professor at University of Buenos Aires and member of Corriente Villera Independiente, or CVI, works on improving villas without government aid. His organisation fights for urbanisation and social equality through an anti-capitalist, leftist social movement.

Bokser is well aware of the city’s under-spending, and is clear about why it happens. “They spend less than they have budgeted for, and that is a political decision, it’s not an anomaly or that something went wrong. If they wanted to do it, they would have done it already.”

Bokser works with neighbours like Natalia Molina from Villa 21-24, in Barracas, a few kilometres south of the Casa Rosada. She said they’re much better off in 2015 than they were when she was growing up. As a child, she and her family would go weeks without power, and had to walk ten blocks to get clean water. She now lives with her three kids and husband Roberto with running water, electricity, and a patio for her seven-year-old daughter and enormous white dog to play outside.

“But it is the neighbours who have built all this,” Molina said. “It’s not like the government came and said ‘there’s a plan to build a water network, there’s a plan for a power grid’.”

Any materials provided, she added, are “low quality building materials, that are not going to last through time.”

Alvaro Arguello worked on the 2009 urbanisation law for Villa 31, and is still campaigning for its implementation. He said there seems to be more money spent on patching up emergency situations than building infrastructure in neighbourhoods like Molina’s.

The number of people applying for emergency aid, or “emergency housing stipends”, according to ACIJ, rose almost 600% since 2006. In response, the city has increased the amount allocated for emergency situations by more than 200%, according to an annual report from CEYS, the Economic and Social Council of Buenos Aires. The report says that the increases in emergency funding have not resolved or reversed these temporary living conditions

Arguello explained that in the long run, it would be cheaper to build infrastructure housing than to keep paying for temporary subsidies. The increase in emergency funding, he said, feeds the cycle of poverty.

“The [housing] policy is not designed to resolve emergency situations,” Arguello told The Indy. “The local government says ‘every city in the world has a housing deficit’ which is partly true, but what is happening here is that, due to an absent state, the issue is getting worse, year after year.”

The Reasons

Arguello explained that most politicians publicly support urbanisation. But the word “urbanisation” isn’t explicitly defined in the laws, complicating discussions between parties.

“They have different visions about how to make these things better,” he said. Who will pay? Who are the recipients? What role will different people play? were some of the questions raised when negotiating the Villa 31 law.

Arguello’s colleague, Rocío Sanchez Andía, was deputy of the housing commission from 2009 to 2013, and helped organise and present the 2009 urbanisation law for Villa 31. Andía is a member of Coalición Cívica para la Afirmación de una República Igualitaria or CC-ARI, a social-liberal party founded in 2002 that does not see eye-to-eye with either city Mayor Mauricio Macri or President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

Sánchez Andía does not blame the law for ambiguity. She mostly points the finger at a lack of leadership by both the city and national governments.

“If we have organisations that are fighting and are willing to move forward, what’s missing? Political will,” she said. “There’s no decision to abide by the urbanisation law, no decision to abide by the constitution.”

She said that the city and federal governments have “different outlooks and different administration styles” but are able to work together when it comes to clearing real estate.

In 2014 for example, city police and national gendarmerie joined forces and bulldozers, to demolish homes of informal settlers, leaving 1,800 people homeless. They had moved onto the state-owned land six months earlier, demanding urbanisation after they say the government failed to deliver on a 2005 law to develop nearby Villa 20.

The razing came one week after the murder of 18-year-old Melina López nearby, allegedly by villa residents. This informal settlement, provisionally named Villa Papa Francisco, was outside of areas covered by the existing urbanisation laws, thereby removing protection against eviction.

There were attempts at dialogue for months but the city’s Social Development Minister, Carolina Stanley, later said they were not willing to “negotiate with those who break the law”. The possibility of economic aid to settlers was quickly also out of the question, and their homes were razed to the ground.

Election Time

The neglect of the villas seems to cool down during elections. Macri ran his 2007 campaign on the promises of 10km of subte lines per year, one policeman on every corner, and urbanising the villas. He projected that in ten years, you could urbanise the entire capital.

“These settlements should be gradually urbanised and integrated into the rest of the city,” Macri said in his 2007 campaign. He pledged “open streets so you can have access to an ambulance, rubbish collectors, and the police”, as well as the extension of sewer and water utilities, land rights, and to build permanent housing.

Daniel Filmus and Pino Solanas, opposition candidates in the last mayoral race, published a 2011 evaluation of Macri’s promises. It painted a significant shortfall for housing. “From his promise of 40,000 homes, only 350 were built,” Filmus said in the assessment.

The city government points to steps it has taken to urbanise, even if it is not what neighbours envisioned. Last August, more than 200 volunteers gathered to “urbanise” the Cildañez neighbourhood, or Villa 6, in southern Buenos Aires. The group, according to the Buenos Aires government website, painted 140 houses, planted 350 trees and 600 plants. A “citizens pact” was signed, a commitment from residents and the government to work together in the transformation process.

“If we all work together, we can make a better future for all, especially for our kids, convinced that they can have more opportunities than we had,” Macri said at the event.

Yet this brand of urbanisation is not what neighbours have historically blocked streets and protested for. Molina recalled events like the one in Cildañez in her own neighbourhood, but never a permanent solution.

“The solution is not fixing a lane or putting cement and covering a hole, and that’s it. That’s not urbanisation,” she said. “Because the officials come in, they make promises at election time, they come round to buy some votes, and then they disappear and the problems remain.”

Stigmas and Incentives

Molina supposes that the lack of commitment to urbanising reflects a lack of support for the residents. She said there is a myth about villas, a dearth of understanding that is shaped by people who have never been there. For years, she has felt unable to integrate into a city “that puts you in a different dimension and that excludes you, based on the fact that you live in a villa.”

“There’s more than what the media shows,” she says, referring to the dominant stories about gangs and drugs. “Here we also have people who want to better themselves, who do so every day, despite us not having a dignified wage.”

She used to blame herself: “Maybe I don’t make enough of an effort, that’s why I live the way I live, or maybe I deserve this?” she remembered. But doubt shifted. She found an answer, and it was not to leave her neighbourhood.

“I realised there’s another reality worth fighting for. That’s the reality I will continue to build together with my neighbours to be able to leave a better place, a better future for my children and for the children of all the villa residents,” Molina said. It is a misconception that people are always looking for a way out of the villas, she explained. There is a culture, a physical and emotional closeness, that does not exist in other parts of the city.

“You can say ‘well, I’m off somewhere’ and I know my neighbour knows I’m gone, and he will look after my house,” she said. “Here you know most of your neighbours – maybe in the city you may live next to someone for 50 years and don’t know that person, maybe in the same building.”

But even if they do not want to leave the villas, some residents fear that eventually, they will be forced to. Mackoviak says Villa 31, with its prized location for real estate, is especially vulnerable.

“They want to evict us from this place because it’s very sought after, it’s the most expensive part of the city,” she said, adding that she is worried about her area becoming “Puerto Madero 3”.

The start of this process, ironically, could be setting up title deeds for villa residents. By handing over land rights without proper infrastructure and support, ACIJ’s Benítez says people living on this valuable state-owned space might be incentivised to sell their property. In places like Villa 31, a stone’s throw from the Four Seasons and luxury restaurants in Puerto Madero, this brand of urbanisation could be lucrative for real estate developers.

“If the villa is located in an area that is very valuable to the urban space, it will start to get gentrified,” Benítez said.

There are also those within the villas who oppose idea of urbanisation. Those sitting on their hands are landlords who profit from a recent boom in population, as internal and international migrants relocate to Buenos Aires.

The number of people living in villas grew by more than 50% between the 2000 and 2010 censuses. The actual amount is likely much higher than reported, since many residents are recent immigrants and are not documented. More people meant a bigger demand for housing, and a huge opportunity for landlords. They unofficially rent to multiple families, and control the price of housing. Some of these landlords own 20 homes, and run an unregulated, lucrative system, which CEYS called “predatory” in their 2015 annual report. The urbanisation laws would bring regulation to the villas, and one new house per family, ruining profits for some landlords.

Walls Rising

Mackoviak could barely be heard over nearby drills as she spoke to the Indy in CVI’s abused women’s shelter. Villa 31 has been buzzing with construction lately, but again, not in a way locals hoped for. A four-metre wall is slowly being built on the side facing the upmarket Recoleta neighbourhood. It will separate the villa from a nearby highway and train tracks.

Mackoviak’s room is less than 90 metres from the tracks. Construction workers line both sides of the tracks, just feet from the only bus stop.

“In a couple of months it’s going to be like the Berlin Wall. We’re going to have a wall we can only cross using that bridge, and that’s it,” Mackoviak said. There is already a wall on one side of the highway, at least one metre tall, with a fence on top. Mackoviak described it as a way to keep them out of Buenos Aires society, rather than integrate them. She wonders why they would build a wall instead of a park.

“It looks like you’re a prisoner when you get close to the wall and you’re behind the fence looking at the cars drive by,” she said. “Like if you were in a jail looking out from the other side.”

The justification was safety. “We’re going to make this bigger so the trains can go through here, we don’t want any accidents,” she said quoting the city government’s logic.

“That’s a lie. There has never been an accident in that crossing… there’s always people’s lack of care and they’re not going to stop accidents from happening just by putting up a wall or a pedestrian bridge.”

Moving Forward

Julian Bokser of CVI laughs when asked about his hope in the urbanisation laws, almost spitting out his coffee at the CVI-owned La Dignidad café in Villa Crespo. He explained that many people, especially foreigners, expect something to happen because a law exists.

“That’s not the way it works here,” Bokser said. “The law was an achievement, but our hopes don’t lie solely on what happens with legislation.”

Bokser says the CVI is not hanging around. The group often shoulders the physical and financial burden of rebuilding villas, working with residents, building everything from nurseries to healthcare centres, and a shelter for abused women in Villa 31. He says they focus on the small improvements. They exist, he said, so people can fight for change.

Bokser, to put it lightly, is not optimistic for upcoming presidential elections. Macri, the current city mayor blamed for his inaction, is running for president in October. Macri’s PRO party could not be reached for comment on his record with villas, or his campaign platform regarding the issue.

But Benítez of ACIJ held on to hope through public awareness. “It’s slowly taking a more important place in the public agenda,” he said. “More people are becoming aware that they are people that have rights.”